Bella Ifasola

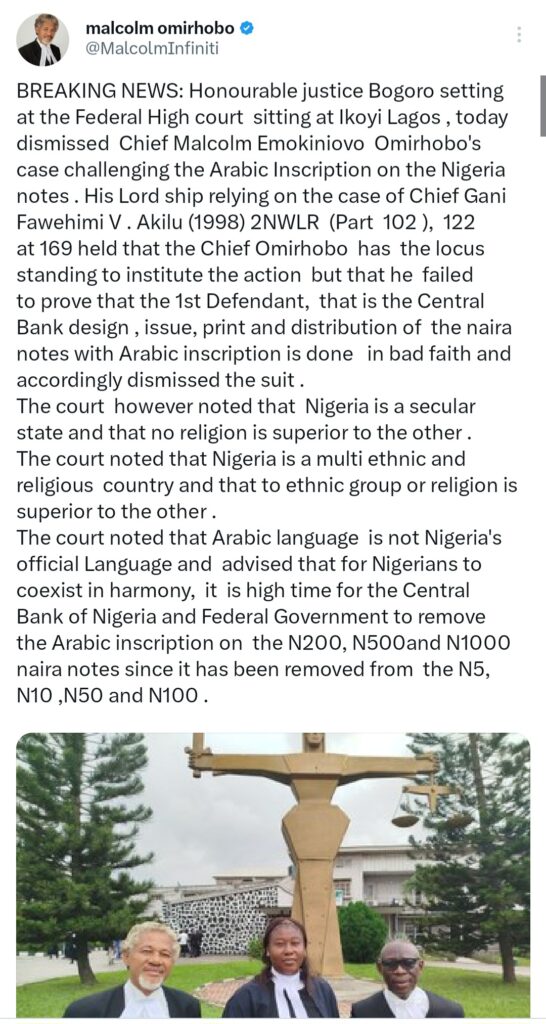

Lagos – A Nigerian Federal High Court sitting in Ikoyi, Lagos, on Tuesday, dismissed a case brought by Chief Malcolm Emokiniovo Omirhobo challenging the inclusion of Arabic inscriptions on the country’s currency – naira.

Citing the precedent set in Chief Gani Fawehinmi vs. Atiku (1998) 2NWLR (Part 102), 122 at 169, presiding judge, Justice Yellim Bogoro ruled that while Omirhobo has the standing to bring the action, he failed to provide sufficient evidence that the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) acted in bad faith in designing, issuing, printing, and distributing the naira notes with Arabic inscriptions.

Consequently, the court dismissed the suit.

In statement shared on X, Omirhobo, a Lagos-based lawyer, stated that the court, however, noted that Nigeria is a secular state and that no religion is superior to the other.

The attorney said the court stated that Nigeria is a multi-ethnic and religious country and that no ethnic group or religion is superior to the other.

“The court noted that Arabic language is not Nigeria’s official language and advised that for Nigerians to coexist in harmony, it is high time for the Central Bank of Nigeria and Federal Government to remove the Arabic inscription on the N200, N500 and N1000 naira notes since it has been removed from the N5, N10, N50 and N100,” he wrote via X @MalcomInfiniti.

A muslim group in the country, Muslim Rights Concern (MURIC), hailed the judgment as “far-reaching, profound, didactic, and monumental.”

In a statement released on Tuesday by the group’s Executive Director, Prof. Ishaq Akintola, the organisation expressed the organisation’s satisfaction with the outcome, adding that the case, which began in late 2020, has finally been put to rest with the judgement.

“This is sweet victory. Once again, the Nigerian judiciary has demonstrated courage, intellectual excellence and jurisprudential exactitude. This judgement is far-reaching, profound, didactic and monumental,” the statement said.

Akintola recalled that in their media release of November 16, 2020, the group told the plaintiff (Omirhobo) that his approach was not only naïve, but pedestrian and kindergarten.

“Muslim-haters always oppose anything that has to do with Islam or Muslims. The case has proved that we own this country together. Nobody is going anywhere for anybody. Nobody can Shugaba Nigerian Muslims from their fatherland. We love Nigeria and Nigeria will continue to accommodate both Christians and Muslims,” he said.

“Even Muslims cannot wish away the Christians. That is the Nigeria we want. We must tolerate one another. We reject a situation in which some people will seek to expel Muslims, persecute them or turn them into underdogs and second-class citizens. Nigeria is for all of us. Neither shall we oppress people of other faiths. We want to live here in dignity with our heads raised up high in the air.”

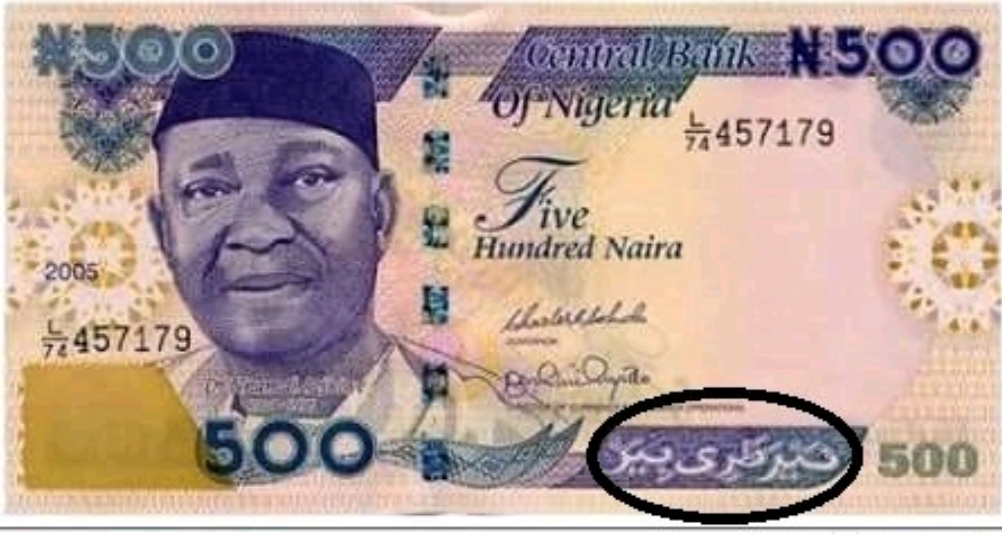

– Arabic inscription on the naira –

Long before the British colonial government thought of amalgamation — or brought Western education to Nigeria — Arabic script had been introduced to Hausaland (in modern-day northern Nigeria) by traders and scholars from across the Sahara, according to a research by TheCable news agency.

The proper term for this ‘Arabic sign’ is Ajami. It is an Arabic-derived African writing system.

The Hausa people used the Ajami script to write in Hausa language.

In much of Eastern Africa, Arabic-derived script is used to write Swahili, although the language itself is Bantu-based.

Since African languages involve phonetic sounds and systems different from the Arabic language, there were adaptations of the Arabic script to transcribe them.

This is similar to what has been done with the Arabic script in non-Arab countries of the Middle East and South Asia, with the Latin script in Africa or with the Latin-based Vietnamese alphabet.

The ‘Arabic sign’ on the naira is actually Hausa language written in Arabic script.

As explained earlier, in the pre-colonial era, the Hausa people took the Arabic script and made it their own.

A typical northerner can read Ajami even if they do not understand the Latin script that is used for English.

The northern part of Nigeria did not embrace Western education early, and there is a strong resistance to it in many parts till today.

But most northerners are versed in Ajami, having undergone Arabic-based Quranic education as children.

The argument against the Arabic inscription on the naira notes is that it is a violation of sections 10 and 55 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Section 10 of 1999 Constitution reads: “The Government of the federation or of a state shall not adopt any religion as state religion.”

The notion is that Arabic and Islam are the same, and this has led to accusations that the Arabic “symbol” on the naira connotes religion and promotes Islamisation.

However, section 55 specifies that the country’s affairs must be conducted in English, Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa.

Since Ajami script is in Hausa language and is not a symbol of Islam or any religion, many will argue that no law has been violated.

Nigerian laws are silent on the script for writing, although the most common is Latin.

In February 2007, the government removed Arabic script from some lower-denomination notes. It said that Ajami was no longer necessary because most Nigerians could now read and write in English.

The government also said it removed Ajami in order to conform to Nigeria’s 1999 constitution.

In 2014, the Goodluck Jonathan administration issued a new N100 note to commemorate the 1914 amalgamation.

On the previous banknote, the words “Naira Dari” — Hausa for “one hundred naira” — appeared in Ajami.

Now, the Hausa was printed, like the Yoruba and Igbo, in Latin letters (English).

This was highly controversial and was viewed in religious and political contexts.

Currently, there is Ajami script on N1,000, N500 and N200 notes.

KOIKI Media bringing the world 🌎 closer to your door step