President Bola Tinubu says his plans will fix the myriad problems of Africa’s most populous country. But with rampant inflation forcing many citizens to forego basic necessities, they’re low on patience.

For much of the past half-century, Nigeria, with its vast population, cultural influence, entrepreneurial drive and abundant natural resources, had the potential to one day become Africa’s economic powerhouse.

But it couldn’t shake off the problems holding it back: an economy so hooked on oil production that job-creating industries outside of raw commodities are barely a rounding error in the nation’s export statistics; a country where more than nine-tenths of the employed work in the informal sector, and where the state is less a provider of public goods than a machine for distributing oil wealth as a form of political patronage. Nigeria lives up to its reputation as a nation of entrepreneurs, but often not by design: The government’s failure to provide for people’s basic needs means citizens must hustle in search of things as simple as water, electricity, education and security as best they can.

Even before Covid-19 aftershocks and the war in Ukraine sent global inflation rocketing in 2021, faltering oil production meant Nigeria was struggling to generate enough income to cover a vast import bill. The government turned increasingly to foreign debt, leaving it exposed when the inflation blowup pushed interest rates higher and the dollar strengthened.

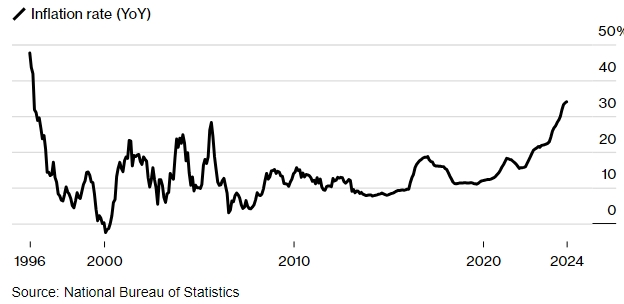

By mid-2023, most of the federal government’s revenue was being spent on servicing the national debt and a shortage of foreign currency was asphyxiating business. Newly-elected President Bola Tinubu loosened currency controls and canceled fuel subsidies, sending domestic inflation through the roof. In the traumatic reckoning that’s followed, the poor have suffered most. The economy, Africa’s biggest in official terms as recently as 2022, has tumbled to fourth place behind South Africa, Egypt and Algeria — a nation with less than a quarter of Nigeria’s population.

Nigeria’s Inflation Rate Is Nearing a Three-Decade High

It’s fanned protests, pushed millions into poverty

This year, the country has witnessed stampedes for food aid, a spike in calcium deficiency and other forms of malnutrition, and job losses as foreign companies packed up and left. Protests erupted in early August. Crowds chanted “we are hungry,” and demanded that Tinubu restore the fuel subsidies and reverse other unpopular reforms. Curfews were imposed in some areas, and more than a dozen people protesting peacefully were killed by the security forces, according to Amnesty International.

To Tinubu, known locally as the jagaban, or one who leads from the front, his policy prescription is painful but necessary. The plunge in the naira has narrowed the gulf between exchange rates on the official and parallel markets. Some of the investors who pulled money out of Nigeria in recent years have been signaling a greater readiness to risk their capital again. In Tinubu’s ideal scenario, they’ll return in sufficient numbers to replenish foreign reserves. With a depreciated currency, Nigeria’s non-oil exports, such as they are, would get a welcome boost.

It’s not certain that Tinubu’s compatriots are willing to wait. He won a disputed election in February 2023 with just 35% of votes cast and is unpopular among young Nigerians who, more than ever, are keen to “japa” — a word meaning to escape, or emigrate, in Yoruba, one of the many languages spoken in Nigeria.

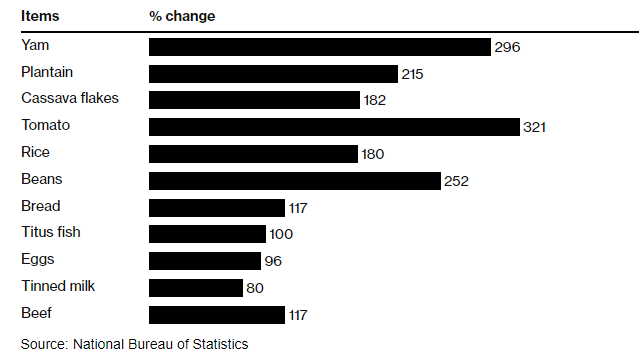

Economic Crisis

Nigeria had more people living in poverty than any country bar India last year. Even before subsidies were pulled and the currency tanked, citizens were often doing two or three jobs to get by. When prices of staple foods went through the roof, many could no longer afford things like eggs, cooking oil and meat. Some resorted to buying the lowest-grade rice that was once thrown away or used to feed fish. Tinubu’s government began to provide food and cash handouts to the most vulnerable, but the scope of the largesse is limited by the government’s means.

Tinubu says he’ll kickstart the economy by investing more in infrastructure and making it easier and cheaper to do business. His plans include cutting the corporate tax rate, bringing millions of people in the informal sector into the visible, taxable economy, providing cheap financing to small and medium-sized companies, and selling state assets.

Currency Dysfunction

Under Tinubu’s predecessor, Nigeria’s government sought to relieve selling pressure on the local currency by implementing one exchange rate for government transactions, a different one for exporters and investors, and yet another for travelers and small businesses. The result was a lively street market for dollars, currency speculation and a big dose of confusion and uncertainty that made it difficult for businesses to budget and plan.

Tinubu removed the tiered exchange-rate system and orchestrated two sharp devaluations that saw the currency slump by 70% to a record low. The central bank has raised rates by 8 percentage points since February to 26.75% to try to arrest the naira’s decline.

Oil and Fuel Shortages

Oil exports are Nigeria’s economic lifeblood and the biggest source of government income, accounting for 81% of exports in the first quarter of 2024. But crude production has declined since 2020 because of widespread theft and vandalism in the oil-rich Niger Delta as well as weak investment in new and existing oil fields. A woeful maintenance record at the country’s refineries created a bizarre situation in which the continent’s biggest oil-producing nation spent $23 billion in 2022 to import petroleum at international market rates, and a further $10 billion on subsidies so the population could afford to buy fuel. Tinubu is hoping to put an end to this vast waste by stimulating investment in onshore fields and refining more fuel from local crude thanks to a vast new facility in the commercial hub of Lagos. For the time being, the new plant will be fed using imported crude.

Power Cuts

Nigeria’s power stations should be supplying about 13 gigawatts based on their installed capacity, but plant breakdowns, shortages of natural gas and a lack of transmission lines means fewer than 4 gigawatts are typically available. Constant outages have led businesses and households to resort to noisy diesel-fired electricity generators — if they can afford them.

To save money and make the power sector more attractive to investors, Tinubu’s administration earlier this year removed some of the government subsidies that made electricity more affordable for urban users, and prices more than tripled.

Chronic Insecurity

Nigeria’s police are poorly trained, under-equipped and too few in number to protect the population. The country’s overstretched armed forces — already grappling with a war against Islamist insurgents in the northeast — are often called in to help with civil matters such as hunting down kidnappers, thwarting oil theft and resolving communal disputes, especially in rural areas.

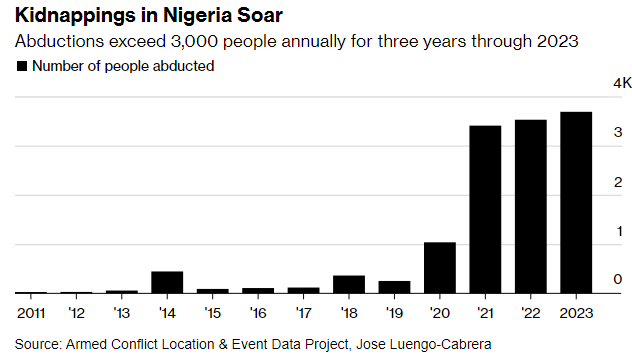

The Islamist militants in the northeast as well as bandits in the northwest and secessionists in the southeast largely operate with impunity, entrenching the sense of generalized chaos and lawlessness. Kidnapping-for-ransom has become a thriving industry. Almost 5,000 people have been abducted since Tinubu took office, according to Nigerian research firm SBM Intelligence. While many of the kidnappers target people in wealthy urban neighborhoods, abductions are far more frequent in the northwest of the country, where motorcycle-riding gangs toting AK-47 assault rifles ransack villages and demand money from farming communities to access their land. Sometimes ransoms are paid and hostages are released. Occasionally, they manage to escape.

Nigerians tend to have little faith in their system of justice. Cases can take years to be decided and the prisons are full of people awaiting trial. Corruption is rife among senior magistrates and judges. Frustrated crime victims sometimes mete out personal revenge, feeding the cycle of violence.

President Tinubu has pledged to tackle insecurity by overhauling and expanding the 300,000-strong national police force and other law-enforcement agencies, and providing them with better training and equipment.

Kidnappings in Nigeria Soar

Abductions exceed 3,000 people annually for three years through 2023

The Backdrop

Nigeria owes its existence to British colonial administrators who sketched the contours of today’s nation and brought it into being in 1914 by fusing two regions into a single entity. The merger brought together more than 250 ethnic groups speaking over 500 languages that otherwise would never have been in a union. The country had a tumultuous ride after independence in 1960, punctuated by a succession of military coups as elites from the largely Christian south tussled for power with the mostly Muslim north. The new nation was traumatized by the Biafra war of secession in 1967-1970 in which between 500,000 and 3 million people were killed.

In colonial times, public service jobs were regarded by many Nigerians as an opportunity to get one over on the British through self-enrichment, and this tradition continued after independence. Federal and regional governments diverted national wealth into the hands of local elites to secure their support. Government jobs, oil income and tax revenue were often doled out as a form of political patronage, with little left to fund public services and investment projects.

Prices of Nigerians’ Favorite Food Items are Surging

Annual food inflation for selected items in June

What happens now?

Tinubu already touched the brakes on his economic overhaul in August 2023, when he restored some of the fuel subsidies that had been scrapped two months earlier. He’s promised further measures to help poorer Nigerians, with a boost to social welfare programs and the national minimum wage — although the latter is unlikely to move the dial for the majority of his compatriots who work in the informal sector.

In late July, a few days before demonstrations erupted nationwide, Tinubu issued a statement in which he accused the civil society groups mobilizing the protest movement online of placing “their selfish ambitions above the national interest.” The comment appears to have gained little traction with Nigerians who’ve grown accustomed to news stories about government officials flaunting lavish lifestyles and educating their children at elite private schools in Europe and the US.

Before long, Tinubu will need to show Nigerians that their hardship was worth it, and that he’s ready to transfer some wealth from the elites who put him in power, and who profit most from the status quo. For now, foreign investors are waiting to see if his policies will survive the political turbulence they’ve triggered.

KOIKI Media bringing the world 🌎 closer to your door step