By DANIEL OJUKWU via Foundation for Investigative Journalism

Police extortion is commonplace in Nigeria, so it did not surprise me when, in November 2023, some Nigerians complained about how policemen demanded N50,000 to issue police character certificates (PCC) to them.

They were gearing up for an international trip, but their host made possession of the certificates a compulsory requirement for admission into a programme in the country. This decision put them at the police’s mercy.

“It costs N30,000 online, but if you don’t register through a police officer, they would ask for an additional payment at the point of capturing,” a source told me of the PCC. “The police don’t even need to see you. They would send you the certificate.”

This information stuck with me, and I began wondering: if the police do not vet the identities of whomever they hand these certificates to, prisoners can obtain them, too. After months of research, I put this theory to the test and succeeded.

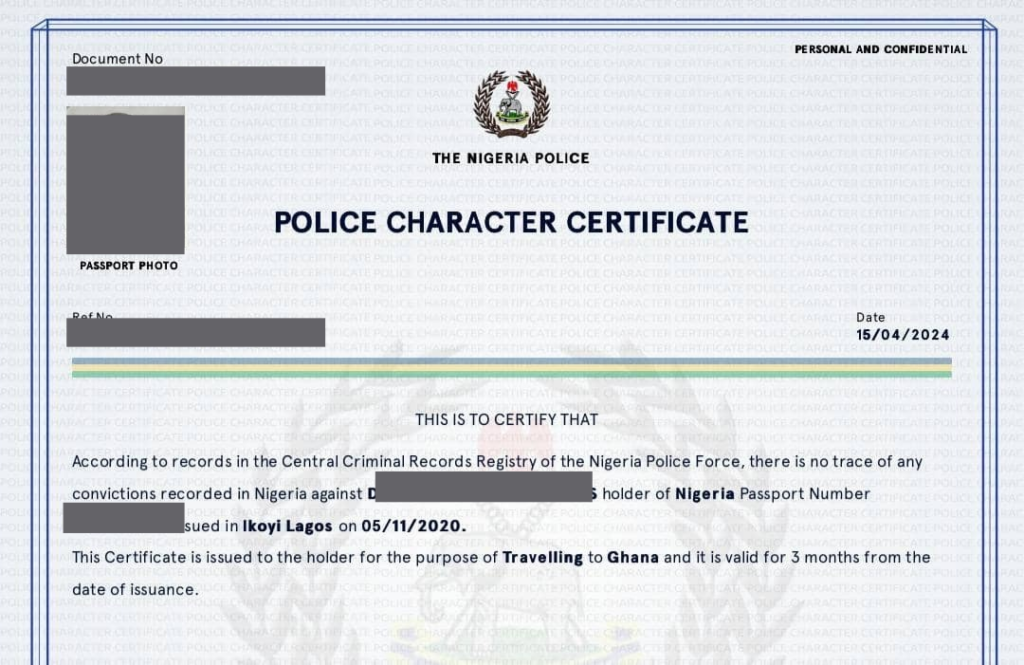

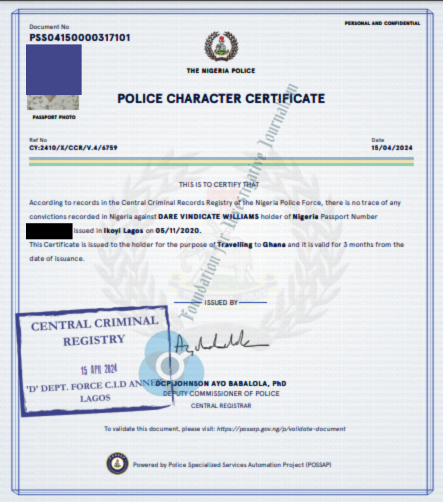

With the help of DSP Stella Agidin, a police officer attached to the Force Criminal Investigation Department (FCID), FIJ was able to use the passport data page of an inmate of the Kirikiri Medium Correctional Facility in Lagos State and a fake passport photograph to obtain a PCC stating this inmate, who had spent almost four years in prison and was still incarcerated as of press time, was cleared by the police to travel to Ghana.

HOW IT STARTED

When sources first came to me in November, they had uncertainty decorating the words they spoke. While some had found the possap.ng website to apply for their certificates, others thought it best to go to the FCID physically.

In the end, the police extorted money from all of them regardless of the approach they took.

“Those of us who paid N30,000 online were told to go for capturing at a police station. When we got there, they demanded up to N10,000 to capture our fingers,” the sources said. “For the ones who went to FCID, they charged between N40,000 and N50,000, but one would not need to capture.”

The extortion was obvious, but I had to ask one of the sources how the police planned to issue the certificate without capturing their biodata.

“Stella said she would indicate online that I was a diaspora applicant and with this, I would not need to have my biometrics captured,” the source explained. “I visited the FCID physically to ask questions, and while there, someone directed me to her office. It was our first meeting. She spoke in hushed tones and said if I asked someone else and followed due process, I would pay as much as N60,000, but with her, all I needed to do was send my details on WhatsApp, pay N40,000 and get the PCC in a day or two.”

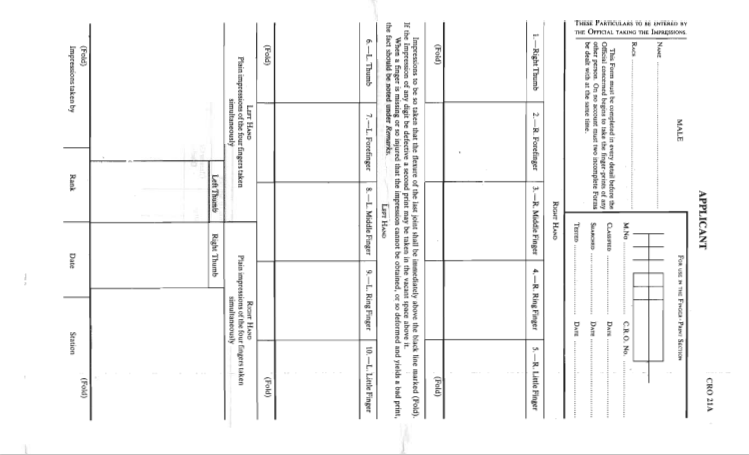

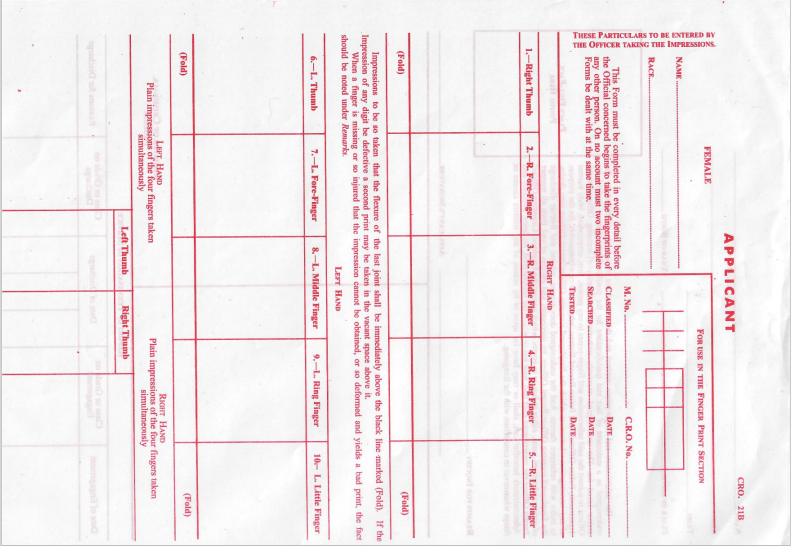

The POSSAP website allows diaspora applicants to download biometric forms for male and female applicants. Stella was not offering applicants a form of any kind, just a workaround to beat the system.

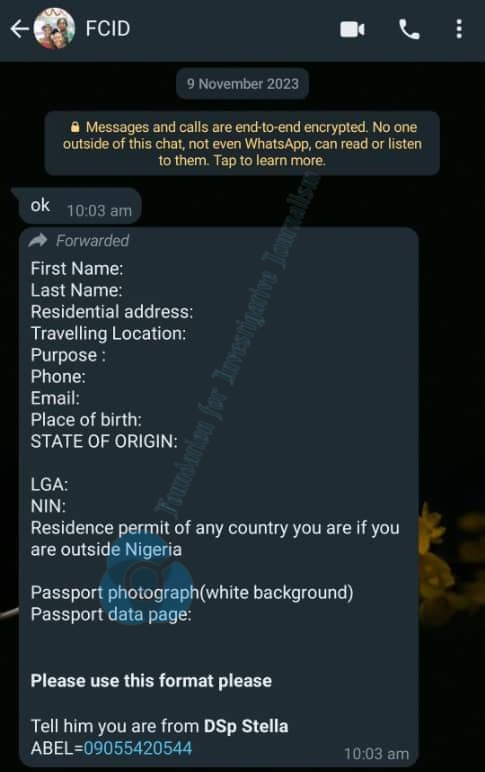

While she was securing paying clients, one Abel Gwazza was facilitating the process. Stella would interact with an individual in need of the certificates and then give them Abel’s number.

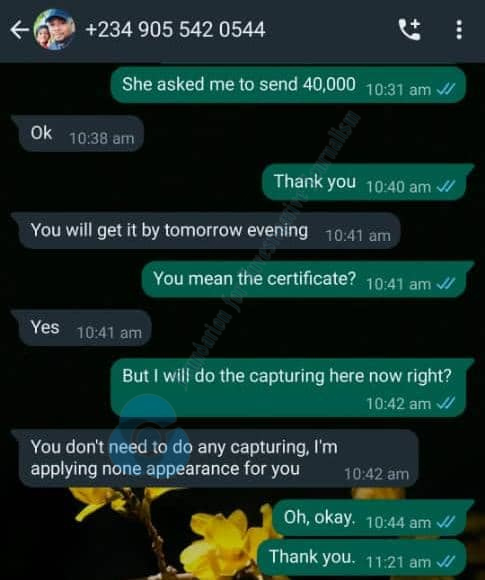

In a WhatsApp conversation with one of the sources, Abel repeated Stella’s words. He said, “You don’t need to do any capturing; I’m applying ‘none-appearance’ for you.”

After conversing with Stella and Abel on November 9, this applicant received their certificate via WhatsApp on November 10. No biodata capture, no vetting, just N40,000 to a willing police officer.

UNCOVERING THE SCHEME

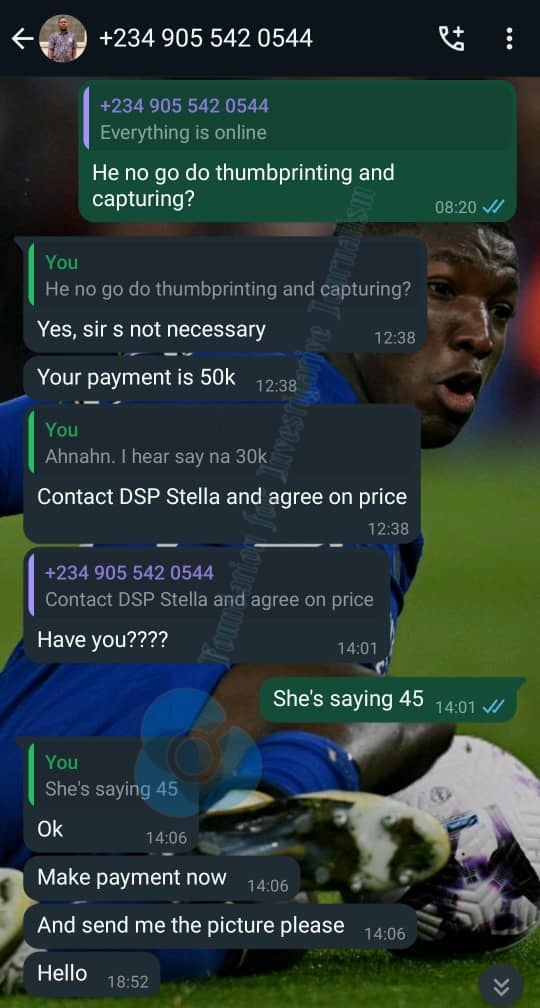

In February 2024, I set out to test the limits of the money-making scheme. To confirm Stella’s involvement, I called her on February 24 pretending to have an unavailable cousin who needed a PCC urgently.

Stella demanded we have the conversation on WhatsApp. During this chat, she sent Abel’s number and asked for a N50,000 payment. After some negotiating, she settled for N45,000.

At this point, I had observed that as was the case with all sources who reached me earlier, the police officer would send an already prepared message detailing what applicants needed to provide, whom they should contact and from whom they should say they were. One did not have to make requests or ask questions before she would send the message. This was normal practice for her.

At the time, I was roaming Nigeria’s streets as a free man armed with the knowledge of corruption in the PCC procurement process, so using my details to get one would have yielded the same result. What I did instead was to engineer a cousin who should have found it impossible to obtain one. My search led me to Kirikiri. The ideal cousin would be an inmate who should definitely not have the means to make themselves available for biometric capturing and who should not have a PCC while still a guest at the facility.

“Send his details,” Stella said when I eventually found one and explained he was unable to speak with her directly.

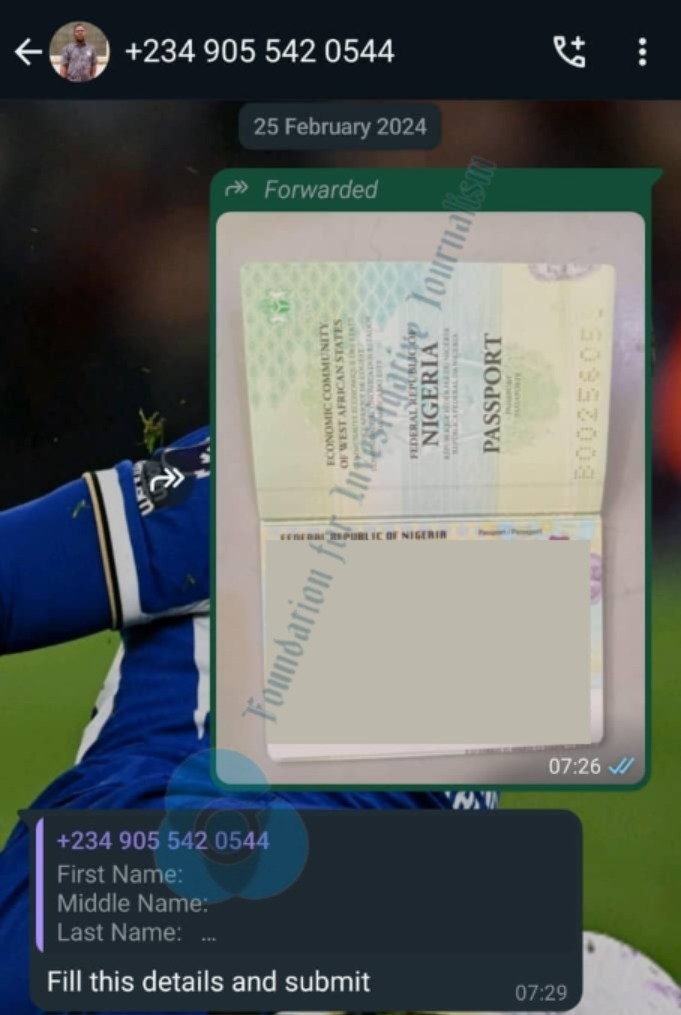

The challenge now was finding an international passport data page for an inmate, getting their biodata and somehow snapping their passport photograph. To achieve this, I contacted several discreet sources and was able to find a virtual copy of an international passport belonging to Dare Williams, a man allegedly arrested during the #EndSARS protests but accused of robbery by the police and doing time while battling ongoing charges.

After confirming the validity of the passport data page and that the inmate was still in custody, I sent the data page of this fake cousin of mine to Abel.

Upon receiving this, the man again confirmed he had no reason to meet with Dare or run checks on him. At this time, a Google search could have shown Abel he was providing services to a man who couldn’t use them. If the background check was as thorough as the police claimed it was, they would have prison and court records.

With his insistence on obtaining a passport photograph, I hit the first brick wall. How do I get a passport photograph of an inmate I had no direct contact with?

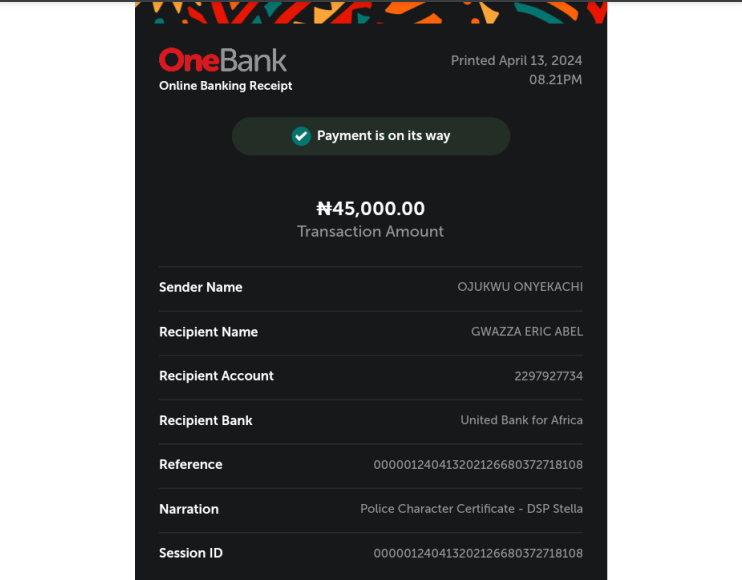

For two months, I explored multiple means of bypassing this one requirement, and then in April 2024, I realised a lookalike would suffice, as all other details – NIN, name, passport and more – were accurate. I found a lookalike, paid on April 13, submitted the passport photograph on April 15 and got the PCC at about 11:11 pm on the same day.

The PCC states that according to the Central Criminal Records Registry of the Nigeria Police Force, there are no traces of criminal convictions recorded in Nigeria against Dare Vindicate Williams, the holder of the passport.

How did the police come to this conclusion without scanning his fingers? It should be impossible. To understand this, I reviewed the Police Specialised Services Automation Project (POSSAP).

POSSAP

On June 2, 2022, the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) launched the POSSAP to serve as a centralised automation system for people to pay for police services and generate income for the force.

At the launching ceremony in Abuja, Maigari Dingyadi, then Minister of Police Affairs, said, “Hitherto, the Nigeria Police has provided specialised services such as requests for police character certificate, police extract, specialized escort and guard services, etc.

“However, the current manual mode of processing the delivery of these services is devoid of the basic tenets of accountability and transparency. For these reasons, the need to automate the processes became imperative.”

Usman Baba-Alkali, then Inspector-General of Police (IGP), agreed with Dingyadi’s position on accountability and fund generation for the welfare of policemen.

Despite the public posturing of the police, I was able to establish the POSSAP was bypassable and many were bypassing it with the help of the police.

After Abel and Stella had secured the certificate for me, I began reviewing how they did it. With access to the POSSAP portal they created for the inmate, I checked to see what stood out.

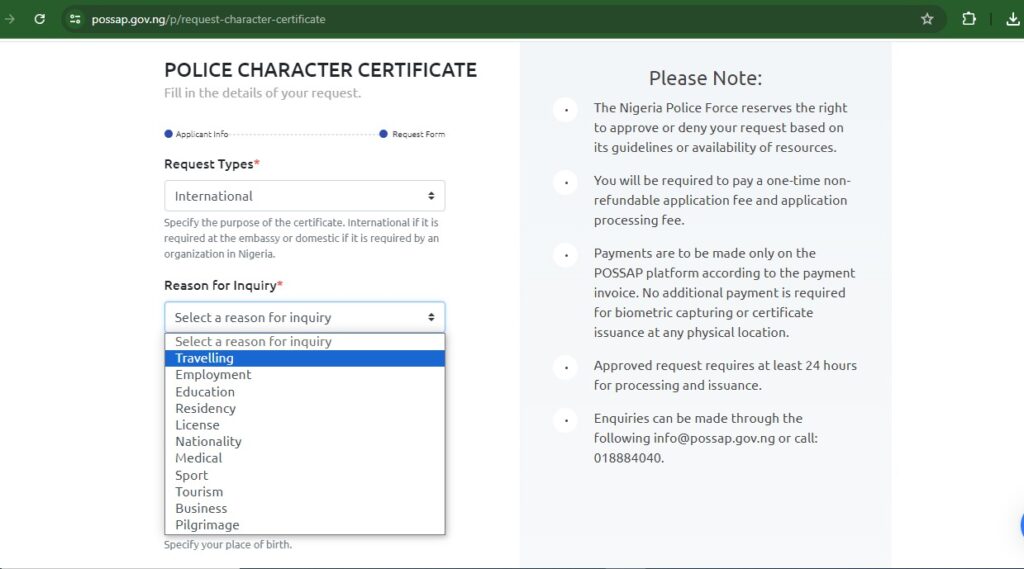

On the page where applicants are to indicate if their request is domestic or international, a textbox sits on the right telling applicants the police could approve or deny requests based on its guidelines or availability of resources. It also tells applicants their N30,000 application fee is non-refundable.

“No additional payment is required for biometric capturing or certificate issuance at any physical location,” the page reads.

In practice, this is untrue, as my experience and those of my sources confirm.

The final point there states approved requests would require at least 24 hours for processing and issuance, but I provided a passport photograph to Abel at 12:25 pm and received the document at 11:11 pm on the same day.

At this point, we had established certain facts: The police would issue PCCs to anyone without biometric verification; PCCs could be obtained in less than 24 hours; contrary to the website publication, police officers are extorting money from applicants; and there is no sufficient effort to vet whoever is getting their hands on these documents.

IT DID NOT START TODAY

Complaints about corruption in the PCC application process did not start in November 2023, and the 2022 introduction of the POSSAP did not rid the system of lapses.

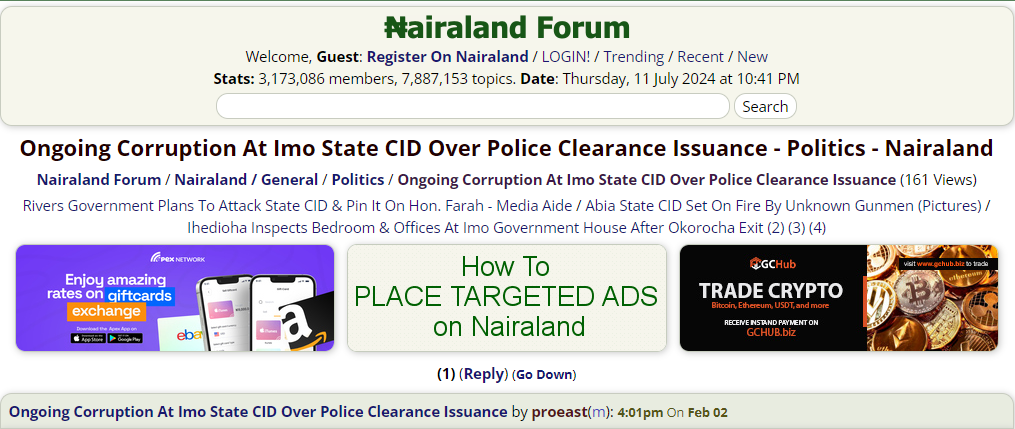

Three months after sources first came to me, an Imo State-based Nairaland user with the username @proeast posted on the forum, detailing how a police officer at the State Criminal Investigation Department (SCID) demanded N30,000 from him after he had already paid the same sum online.

His February 2, 2024 post read:

I applied for a police clearance certificate online and was requested to pay the necessary fees (about 30,000 naira) which I did. When I encountered a system delay, I wrote an email to the secretariat in Abuja, and they swiftly responded. I was excited at their professional conduct and prompt response to my email.

Unfortunately, things took a different turn when I got to the Imo State CID situated at the state police headquarters within the government house, to conduct biometrics. I was directed to meet a lady who was in charge of biometrics. Then I was shocked when she demanded for another 30,000 naira payment. I immediately told her that I have already paid online and was only directed to come for biometrics capturing. Her countenance changed and she told me I must pay the fee or go look for inspector Ogbu**.

I realized she wanted to frustrate me and I left.

It is really saddening and distasteful that in this modern time, corruption still thrives in the open like this. No society can ever develop if corruption is allowed to become so endemic.

In 2022, Leadership Newspaper published an editorial condemning a 700 percent hike in the PCC application fee and the corruption involved in obtaining one. The newspaper said they had found that if police knew one was well-to-do, they would charge as much as N100,000.

In this editorial, the newspaper highlighted that foreign countries take the PCCs seriously, as it helps them ensure whoever is coming in does not pose a threat to them.

SECURITY RISKS

To best understand the importance of verification and due diligence in the PCC application process, I found the curious case of an innocent victim who obtained a certificate they did not know to be fake.

This person had approached one Chinedu Agbosim, a cybercafe owner; Mariam Dauda and Ebighose Anderson in November 2023. These three pretended to be able to provide the service on the police’s behalf.

Unknown to the victim, they were fraudulent, and the UK Embassy flagged the fake certificate they issued, and then banned the victim from entering the UK for 10 years.

For every PCC that is issued, the entity that receives it has the authority to seek confirmation of its authenticity. So, if the police can’t confirm the source of a Nigerian’s PCC, it can lead to a lengthy visa ban. Also my ‘cousin’ can evade lawful custody and go into another country without a hitch just because the police confirmed what they didn’t verify.

Between 2017 and 2022, there were at least 10 major jailbreaks in Nigeria, with thousands of inmates escaping detention all over the country.

In October 2020, an inmate who escaped from Oko prison in Edo State went to his village to kill a witness who had testified against him in court. Two years after that incident, terrorists belonging to the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) attacked the Kuje Correctional Centre in Abuja, freeing more than 600 inmates.

The sect killed a guard, shot sporadically and made a video about it. They claimed the inmates they came for were their members. Like these escapees, several other thousands of inmates have escaped lawful custody all over the country, with the most recent one occuring in Suleja, Abuja, on April 25.

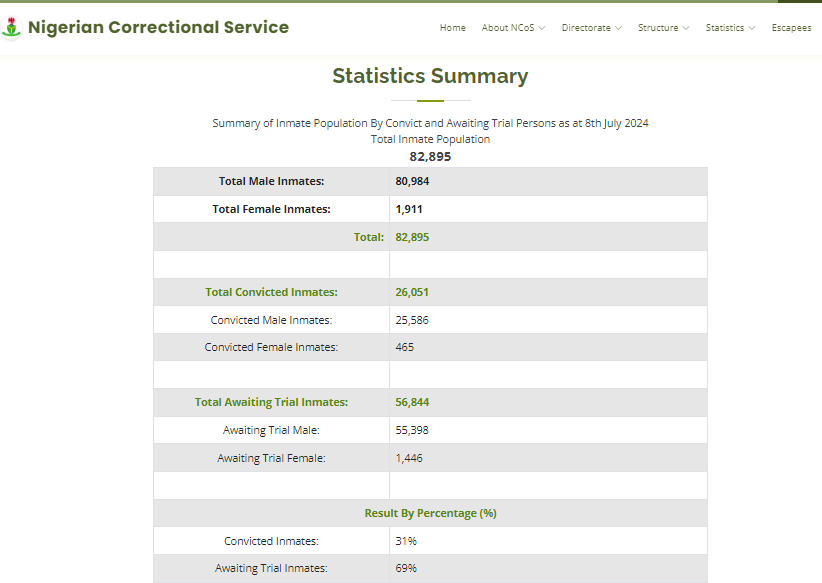

According to the Nigerian Correctional Service (NCoS), there were 82,984 inmates in the country’s facilities, but of this number, 56,844 were awaiting trial, representing 69 percent of the population.

Despite these records, a 2019 report found that with N10,000, anyone could wipe any record of their conviction off the NCoS database. Several reports and sources have also revealed how prison officials swap convicts with innocent Nigerians while transporting them to prison, leaving the convicts free to go wherever they choose as someone else serves their term.

My findings showed that any one of these people supposed to be remanded in custody for murder, robbery, terrorism or any other felony could escape, get a sterling recommendation from the police in a few hours and travel to another country of their choice – all for N45,000.

LAPSES IN ONLINE TECHNOLOGY

During the course of working on this report, I spoke with several insiders in the police and the NCoS.

On condition of anonymity, a member of the NCoS’ staff said he expected the lapses because the police are not qualified to determine who is convicted or not and who is qualified for a character certificate or not.

The source said, “In the early 60s and 70s, the police could have been able to do so effectively, but the correctional services should be tasked with that now. We have the database to vet biometrics and details of anyone. If someone applies and they are supposed to be in jail for a conviction or to await trial, we would immediately know. The police cannot know that until they contact us officially.

“What they may have is details of who has been arrested, but to determine if that person is supposed to be in our custody or not or has a case to answer should be the job of the NCoS. There are court records, prison records and others. It is not just by checking arrest records.”

Another source in the police told me the force lack accurate data. He said the database for arrested persons is only accurate as of 2014. “Anything before then is lost. We don’t have it,” this source said.

The source also said the police do not have enough data on prison inmates to authoritatively say their PCCs are accurate.

“We just assume whoever walks in to apply is a free person. Most escapees use illegal routes to leave the country,” he said.

This source referenced the May 25 launch of a new cybercrime reporting website as evidence of lapses in the police’s digital record-keeping.

The police announced the introduction of https://nccc.npf.gov.ng/ereport/signin to replace https://incb.npf.gov.ng as a cybercrime reporting platform in May. FIJ had reported that the now-defunct platform was volatile and left users’ data vulnerable.

“We blew the whistle long before then, but no one was interested in investing in fixing the problem,” this source said. “When they finally invested in an upgrade, we wanted to shut that old site down, but they wanted it to coexist side by side with the new one so anyone who visits the old one will be redirected to the new one.”

With this information, I checked to see how vulnerable the POSSAP platform was. My first stop was the administrator page.

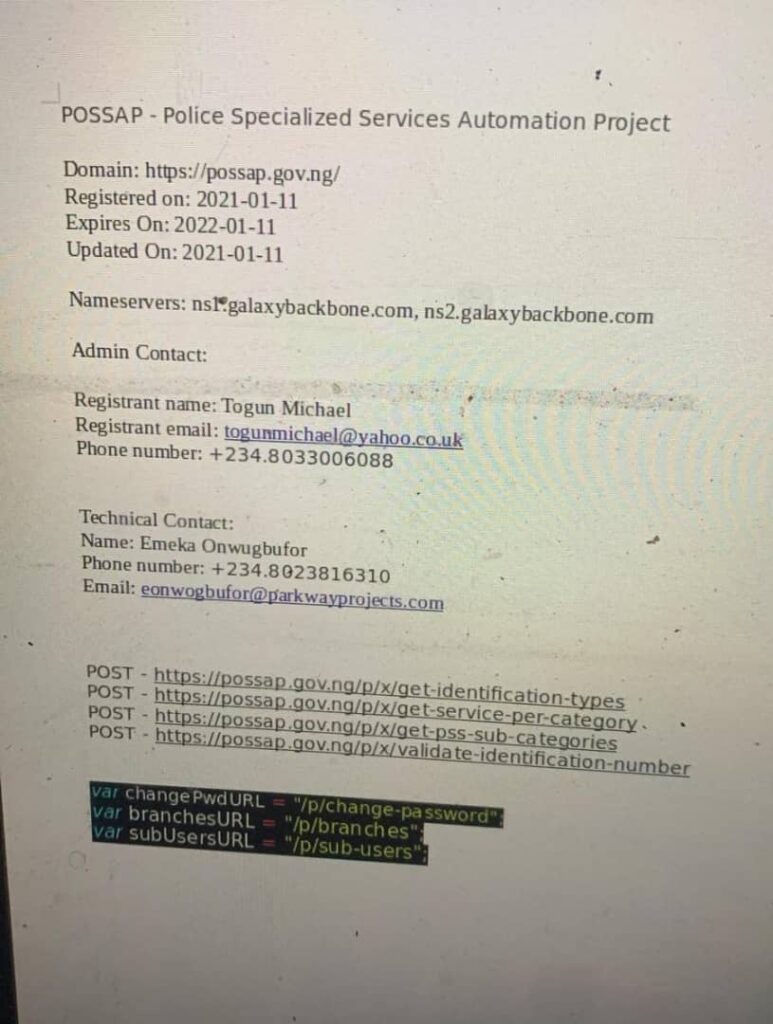

What I found was that the website was registered to one Togun Michael and one Emeka Onwugbufor was listed as a technical contact.

I called Togun, and he said he had no idea how his contact details ended up on the website. He was a police officer stationed in Abuja, and, according to him, he was one of the people involved in creating the POSSAP website in 2021, but he never knew his number would be uploaded.

“You are the second person to ask me this question. I don’t know why my number is there,” Togun said. “I will take this up so it is changed.”

The policeman refused to comment on the quality of the POSSAP and asked that I speak with authorised persons. Onwugbufor did not take my calls.

REACTIONS

On several occasions, I called Muyiwa Adejobi, Force Public Relations Officer (FPRO), but he did not respond to my calls. When he responded to my text message on July 14, he requested that I email him instead.

I sent the email on the same day, but he had yet to provide an official response at press time.

When I called Umar Abubakar, Public Relations Officer of the Nigerian Correctional Services, he said the NCoS had its own database and there was no collusion between the police and the service to bypass the system.

Abubakar said the service operates an open database the police can go through if they want, but he also confirmed there are challenges in record-keeping.

“Some prison facilities have challenges in maintaining electronic records of inmates,” he said. “What we are doing now is having them manually transmit their records to a facility that can upload them electronically.

“We have done backup for them. They snap the records, go to the city centre or send them to the state command to use them for their needed purposes.”

Abubakar said he believes anyone issuing the PCCs to people who should be in custody or unfit for one is doing so illegally and independently of the police, but when I reminded him the process was done on POSSAP with the help of a serving police officer at the FCID, he thanked me for my findings and promised to follow it up for collaborations and effective policing of the country so escapees don’t flee the country through legal routes and pose threats to other countries.

This story was produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation